I just came across a great reference site for zooarchaeology that might be useful to skelephiles of other sorts. It's called Archeozoo, and it's available in English and French.

It's got news, articles, lists of collections, a forum and more. I haven't had the time to explore it in depth yet, but it looks like there's lots of great information. If you're a zooarchaeologist or in a related field, you can sign up to contribute your own articles as well.

It's starting to look like I need to create a links page, doesn't it . . .

It ain't no sin to take off your skin and dance around in your bones. Or to study the bones of other creatures. That's fun.

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Friday, July 29, 2011

A Bone Book Mystery

Some time ago, while I was still an art student, I acquired a few old library sign-out cards from the old days when you had to write your name on a card when you signed out a book, and when it was returned, you'd be crossed off and the card got stowed back in its pocked in the back of the book. I guess the library was tidying up and maybe converting the last few hold-outs to the barcode system. Anyway, they tossed things in a box for students to pick through, because poor art students make art of all kinds of things. Among the ones I got (more out of nostalgia than because I thought I'd actually make anything of them) is this one:

I was intrigued by the title, I think, but the card ended up in a box of miscellaneous things and vanished from my thoughts. I found it a couple of weeks ago, when looking for something else entirely, and decided to investigate. The book is:

Title: Bare Bones: An Exploration in Art and Science

Author: either L.B. Halstead or Beverley Halstead and Jennifer Middleton (perhaps cited differently in different editions?)

Publisher and date: Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1972 and Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1973.

ISBN-10: 0050025147 (not sure which edition this goes to)

ISBN-13: 9780802019714 (again, not sure which edition to goes to)

Size: unknown dimensions, 119 pages

Naturally, this sounds like it's exactly my sort of book. So, now I'm going to track down a copy (ABE lists lots; it's just a matter of deciding which one is likely to be both cheap and in good shape--if it turns out to be a really great book I may look for a pristine copy later).

Stay tuned for an update and a review once I have a copy in my eager hands.

I was intrigued by the title, I think, but the card ended up in a box of miscellaneous things and vanished from my thoughts. I found it a couple of weeks ago, when looking for something else entirely, and decided to investigate. The book is:

Title: Bare Bones: An Exploration in Art and Science

Author: either L.B. Halstead or Beverley Halstead and Jennifer Middleton (perhaps cited differently in different editions?)

Publisher and date: Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1972 and Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1973.

ISBN-10: 0050025147 (not sure which edition this goes to)

ISBN-13: 9780802019714 (again, not sure which edition to goes to)

Size: unknown dimensions, 119 pages

Naturally, this sounds like it's exactly my sort of book. So, now I'm going to track down a copy (ABE lists lots; it's just a matter of deciding which one is likely to be both cheap and in good shape--if it turns out to be a really great book I may look for a pristine copy later).

Stay tuned for an update and a review once I have a copy in my eager hands.

Thursday, June 23, 2011

"Bones With Bling" in Fortean Times

Via Morbid Anatomy (which you should be reading if you like the morbid, odd, and peculiar), there's an article in the Fortean Times on "the amazing jewelled skeletons of Europe," titled Bones with Bling.

I'm not likely to link to Fortean Times very often, but this is an interesting piece about a forgotten part of Catholic Christian history, when supposedly psychic priests would "discover" the bones of saints and martyrs which would then be lavishly decorated as relics. Of course, many of the skeletons had probably belonged to ordinary people--even pagans--but more saintly relics meant greater prestige for the Church and could mean increasing attendance (and therefore wealth) at smaller churches.

Whether these bones belonged to holy people or ordinary people, they certainly make beautiful displays.

I'm not likely to link to Fortean Times very often, but this is an interesting piece about a forgotten part of Catholic Christian history, when supposedly psychic priests would "discover" the bones of saints and martyrs which would then be lavishly decorated as relics. Of course, many of the skeletons had probably belonged to ordinary people--even pagans--but more saintly relics meant greater prestige for the Church and could mean increasing attendance (and therefore wealth) at smaller churches.

Whether these bones belonged to holy people or ordinary people, they certainly make beautiful displays.

Monday, June 20, 2011

OsteoSophy on Etsy

I added intercaps in the name, mostly because it looked nicer on the banner. So, yeah. I opened (another) Etsy shop to sell my new line of copper animal skull jewellery (because I don't already have too many things to do).

Here are the first few items for sale (and after this, I probably won't mention this stuff again, unless I make something really exciting, but I will add a widget or link or something to the sidebar).

First, I made a thylacine (above, posing on a whitetail deer skull), because everyone needs a thylacine. Right?

Then a fox, which I really made for myself. I listed it for sale, but if someone buys it, I'll have to make another for me.

A badger, which never fails to lodge that silly song "badger, badger, badger, badger, badger, badger, mushroom, mushroom" in my head (don't know what I'm talking about? go here).

Finally, a snowshoe hare, because things other than carnivores have cool skulls, too. I've got a whole pile of drawings ready to resize so I can make more--deer, goat, dolphin, bear, various birds, some herps. Eventually I'll add some dinosaurs.

Here are the first few items for sale (and after this, I probably won't mention this stuff again, unless I make something really exciting, but I will add a widget or link or something to the sidebar).

First, I made a thylacine (above, posing on a whitetail deer skull), because everyone needs a thylacine. Right?

Then a fox, which I really made for myself. I listed it for sale, but if someone buys it, I'll have to make another for me.

A badger, which never fails to lodge that silly song "badger, badger, badger, badger, badger, badger, mushroom, mushroom" in my head (don't know what I'm talking about? go here).

Finally, a snowshoe hare, because things other than carnivores have cool skulls, too. I've got a whole pile of drawings ready to resize so I can make more--deer, goat, dolphin, bear, various birds, some herps. Eventually I'll add some dinosaurs.

Thursday, June 16, 2011

Convergent Skulls: Walrus and Elephant

I was watching on episode of Oddities a while ago (a great tv series for skelephiles and other fans of odd stuff), and someone brought in a walrus mandible (actually both mandibles fused). The expert they had look at the bone commented on how similar it was to an elephant mandible, despite the very different diets of the two animals.

That got me thinking about walrus and elephant skulls and the similarities they have evolved, largely due to the fact that both animals need skulls that can support a massive pair of tusks. Of course, there are also a lot of differences, but have a look at these simplified illustrations.

Obviously, these are not to scale. I don't have anything profound to say here, just that it's cool to think about how the bones of animals can be so similar or so different, depending on how they developed.

That got me thinking about walrus and elephant skulls and the similarities they have evolved, largely due to the fact that both animals need skulls that can support a massive pair of tusks. Of course, there are also a lot of differences, but have a look at these simplified illustrations.

Obviously, these are not to scale. I don't have anything profound to say here, just that it's cool to think about how the bones of animals can be so similar or so different, depending on how they developed.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Bone Art: Takayuki Hori

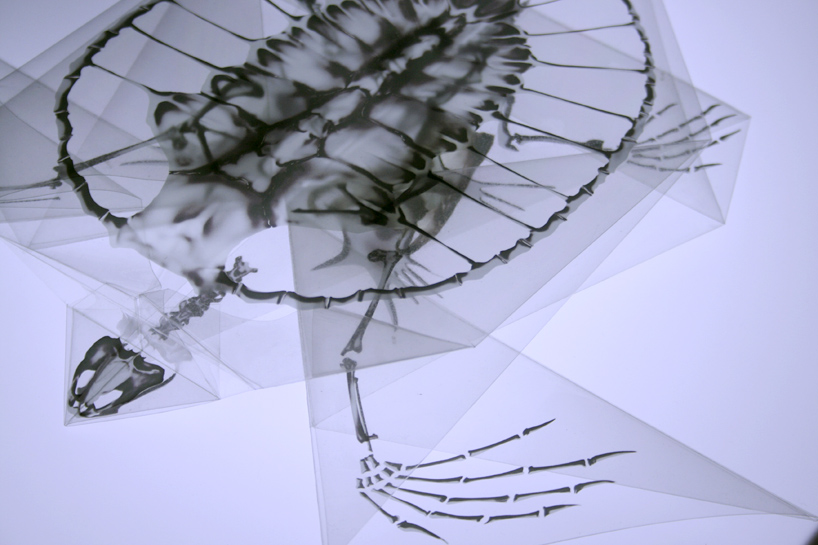

Here's something absolutely breathtaking: "Oritsunagumono" by artist Takayuki Hori.

Each piece was printed on translucent paper and then folded using traditional origami patterns. Some of them have coloured images of trash superimposed on them, as a comment on "the animal's plight to survive in an increasingly polluted and hazardous ecosystem."

The pieces are displayed on a lightbox, with an unfolded version of the image in a frame on the wall behind. See more photographs on designboom. Really, go and look, this work is just amazing.

Some of you may know that I'm also a letterpress printer, and I'm just dying to borrow this idea and letterpress print skeletons on origami paper. I don't know if I will, though, except maybe to make a few for myself.

Each piece was printed on translucent paper and then folded using traditional origami patterns. Some of them have coloured images of trash superimposed on them, as a comment on "the animal's plight to survive in an increasingly polluted and hazardous ecosystem."

The pieces are displayed on a lightbox, with an unfolded version of the image in a frame on the wall behind. See more photographs on designboom. Really, go and look, this work is just amazing.

Some of you may know that I'm also a letterpress printer, and I'm just dying to borrow this idea and letterpress print skeletons on origami paper. I don't know if I will, though, except maybe to make a few for myself.

Monday, May 9, 2011

Book Review: How to Build a Dinosaur

How to Build a Dinousaur: Extinction Doesn't Have to Be Forever by Jack Horner and James Gorman. London and New York: Dutton, 2009.

There are a couple of things misleading about the title of this book. First, it's not really about how to build a dinosaur, it's about the science that has lead up to the possibility that we might someday be able to create a living dinosaur out of a bird embryo. And second, it's not really about bringing anything back from extinction, it's about using the way a growing creature's genetic code sends instructions to its cells to learn about how evolution has progressed and in the process change the development of a chicken so that it grows into something more commonly recognizable as a dinosaur (because, or course, birds are already dinosaurs). There's nothing about tinkering with the DNA itself.

That said, this is a great book, and though it's not entirely focused on bones there is more than enough cool bone science for the curious skelephile. If you're into dinosaurs (and if not, what's wrong with you?), or the evolution of birds, or if you're interested in how embryonic development makes a skeleton grow a pygostyle, say, instead of a tail, you should add this volume to your library. Jack Horner is an articulate and enthusiastic dinosaur guy, and with the help of co-author James Gorman he's written a very readable book that intelligent readers of just about any level of dinosaur knowledge can enjoy.

I would have liked to see a few more illustrations or photographs, but the lack of them isn't really a strike against the book. The most important things get visuals--I'd just have liked to have had a few more things to ponder visually.

Though this isn't a book aimed at a scholarly audience, I do think bone scholars would find a lot to like here. Plus, there are references in the back for each chapter, so the interested can pursue the scientific papers and books that inform the discussion.

I based this review on the 2009 hardcover version that I found remaindered at the local book store. I see, though, that a paperback with a different subtitle (The New Science of Reverse Evolution) came out in 2010. I've no idea if anything else changed besides the title, but if you're going to buy it full price, you might want to go for the more recent edition.

Monday, May 2, 2011

Bone Art: Jessica Joslin

There's a great interview with artist Jessica Joslin over at Hi Fructose magazine. Here's a little snippet that really struck me, though I encourage you to read the whole thing:

There is a strange intimacy in working with bones, and there are often tangible tales about the animal's life embedded within. I know whether it died young or old, if it had arthritis or parasites, if it had broken a bone and if so, how long ago and whether it would have limped. It might have bits of shrapnel embedded, with the bone grown up around it like a pearl--that tells me that it had a run-in with a hunter and survived. Fellini once said, “The pearl is the oyster's autobiography.” If you know how to read them, bones are an animal's autobiography.On my list of artists whose work I would like to own if I became suddenly wealthy, Joslin is pretty close to the top. I could imagine a crazy Victorian house filed with her sculptures (though actually I want a Craftsman house some day).

She's also got a gorgeous new website with many, many pictures of her work. Looking through them all, I really wished for a nice, heavy art book that I could flip through on my couch. And look, there is a book! I'll have to save my pennies and buy a copy.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

Natural History Museums

I was reminded by a post on James Gurney's art blog ("Museum of Comparative Zoology") that natural history museums are a great place to find bones to look at. In addition to the displays of mounted skeletons, many museums--especially the larger ones--have comparative collections that may be available for researchers. Even if they don't, it can be fun to spend an afternoon (or in the case of larger museums, several days) wandering the displays, snapping photos and making drawings.

Gurney wrote about the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, and not only is it a great museum (and on my list of museums to someday visit), it also has a fantastic web site.

Last time I went to the museum closest to me--the Museum of Natural History in Halifax, Nova Scotia, I neglected to take my camera, but I did have my old iPhone 3G, and I snapped a few not-very-good photos for reference.

Sharks! And a horse:

A dolphin:

A small whale:

And a really big T. rex named Sue (on loan from the Field Museum in Chicago):

Gurney wrote about the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, and not only is it a great museum (and on my list of museums to someday visit), it also has a fantastic web site.

Last time I went to the museum closest to me--the Museum of Natural History in Halifax, Nova Scotia, I neglected to take my camera, but I did have my old iPhone 3G, and I snapped a few not-very-good photos for reference.

Sharks! And a horse:

A dolphin:

A small whale:

And a really big T. rex named Sue (on loan from the Field Museum in Chicago):

Tuesday, April 12, 2011

Bone Art: Kate MacDowell

Thanks to a friend's StumbleUpon bookmarks, I came across the incredible ceramic sculptures of Kate MacDowell a day or two ago.

Notice the human skeleton. She has several more along the same lines, as well as other beautiful, surreal pieces. Songbirds perching inside a pair of human lungs, literal clay pigeons, and other wonderful things. Go look at her portfolio, you will be amazed.

Notice the human skeleton. She has several more along the same lines, as well as other beautiful, surreal pieces. Songbirds perching inside a pair of human lungs, literal clay pigeons, and other wonderful things. Go look at her portfolio, you will be amazed.

Sunday, April 3, 2011

Oddities

Last night I was finally able to catch a couple of episodes of the Discovery Channel show Oddities (I'm in Canada, and US shows, if we get them at all, usually get here much later). It's a lot like Pawn Stars or American Pickers--in fact, even the wording of some of the commentary is so similar it made me wonder if they're using the same writers--but set in an antique shop that caters to collectors of, well, oddities.

Aside from being a total blast for anyone interested in weird stuff, there was a lot for a bone collector (or other skelephile) to love. There are plenty of skulls and jarred specimens in the background, and one of the episodes I watched featured the skull collections (mostly human) of one of the employees and his rival, a chiropractor and regular customer. Said employee (my apologies--I haven't got their names stuck in my brain yet) also constructed a Beauchene (or "exploded") skull from a disarticulated skull that his rival/friend brought in.

Very cool. And both skull collectors had fantastic shelving, too! I want those glass-fronted cases for my collection. And for my books. So check it out, and have a look at the website, too, it'll give you a taste of the show, and there are some neat exclusives.

My only quibble is that the episodes are only a half hour each, so there's no real time to delve into the history and background of the objects, or the lives of the proprietors and their colourful cast of customers. Still, an excellent show, and one I might even pick up on DVD if it gets a release.

Skull image copyright Niko Silvester. Please don't use without permission, thanks.

Aside from being a total blast for anyone interested in weird stuff, there was a lot for a bone collector (or other skelephile) to love. There are plenty of skulls and jarred specimens in the background, and one of the episodes I watched featured the skull collections (mostly human) of one of the employees and his rival, a chiropractor and regular customer. Said employee (my apologies--I haven't got their names stuck in my brain yet) also constructed a Beauchene (or "exploded") skull from a disarticulated skull that his rival/friend brought in.

Very cool. And both skull collectors had fantastic shelving, too! I want those glass-fronted cases for my collection. And for my books. So check it out, and have a look at the website, too, it'll give you a taste of the show, and there are some neat exclusives.

My only quibble is that the episodes are only a half hour each, so there's no real time to delve into the history and background of the objects, or the lives of the proprietors and their colourful cast of customers. Still, an excellent show, and one I might even pick up on DVD if it gets a release.

Skull image copyright Niko Silvester. Please don't use without permission, thanks.

Sunday, March 27, 2011

Skeletal Blogroll

If you look to your right, you'll see I've added a blogroll. Woo! The blogs listed are a mix of archaeology, palaeontology and zoology, and they're mostly not all-bones-all-the-time, but they do have a goodly amount of posts relating to bones. If I've missed any, please do let me know (you can leave a comment on this post, for example) and I'll check them out.

Saturday, March 26, 2011

Bone Art: The Evolution of Flight

A few years ago, when I was still in art school, I made a lithograph titled "The Evolution of Flight." It ties in to some stories and comics and books and artefacts I've been working on which will all come together in something bigger once I figure out what shape I want it to take.

But anyway, what's relevant for this blog is that I used bones in it. The print -- as you can see from the image -- is multiple layers of stuff. For those interested, I started with three runs from a litho stone, altering it each time with etching and sanding (that's the wing shape that dominates the image from far away). Then I added two separate runs from aluminum photoplates, made from my own drawings (or handwriting, in the case of the brown layer). One of those plates is a sort of comparative anatomy diagram, which came to mind when I was writing up the book review in my last post.

The image shows four skeletal limbs. The first is a bird:

The next is bat:

Then, of course, human, because this is the evolution of human flight:

And the final one is not from an animal but a flying machine (of my own silly invention) called a pterothopter.

In retrospect, I should also have included a pterosaur wing, though the pterpthopter is acutally named for Pteropus, the genus of bats called "flying foxes" and not for the pterosaurs. Still, it would have been a good thing to have.

The handwriting, incidentally, is bits of a story about a made scientist character who decided to create flying humans. She intended to do so through a combination of selective breeding and prosthetic surgery, but eventually gave up to work on flying machines with human pilots instead (and her neighbours breathed a sigh of relief).

But anyway, what's relevant for this blog is that I used bones in it. The print -- as you can see from the image -- is multiple layers of stuff. For those interested, I started with three runs from a litho stone, altering it each time with etching and sanding (that's the wing shape that dominates the image from far away). Then I added two separate runs from aluminum photoplates, made from my own drawings (or handwriting, in the case of the brown layer). One of those plates is a sort of comparative anatomy diagram, which came to mind when I was writing up the book review in my last post.

The image shows four skeletal limbs. The first is a bird:

The next is bat:

Then, of course, human, because this is the evolution of human flight:

And the final one is not from an animal but a flying machine (of my own silly invention) called a pterothopter.

In retrospect, I should also have included a pterosaur wing, though the pterpthopter is acutally named for Pteropus, the genus of bats called "flying foxes" and not for the pterosaurs. Still, it would have been a good thing to have.

The handwriting, incidentally, is bits of a story about a made scientist character who decided to create flying humans. She intended to do so through a combination of selective breeding and prosthetic surgery, but eventually gave up to work on flying machines with human pilots instead (and her neighbours breathed a sigh of relief).

Wednesday, March 16, 2011

Book Review: Comparative Skeletal Anatomy

Comparative Skeletal Anatomy: A Photographic Atlas for Medical Examiners, Coroners, Forensic Anthropologists, and Archaeologists by Bradley J. Abrams and Pamela J. Crabtree. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2008.

I have a confession to make: when I'm passionately interested in a particular subject, I treat my books on the subject as more of a collection than a library. And what I mean by that is that I have the strong, sometimes irresistible urge to buy every book on that subject, and not just the good ones. And so it is with bone books. Even when a book gets terrible reviews, I want to buy it for my collection. The good side of this tendency is that I'm never really disappointed by a lousy book--it's still a good piece for the collection. The bad side is that I waste money on books that aren't really useful.

By now you're probably expecting me to say how terrible this book is, and I'll get to that, but I should point out that it's not all bad, and there probably is an audience for whom Comparative Skeletal Anatomy will be useful. I can certainly imagine situations where photographs directly comparing human and animal bones would be handy to have. It's just too bad the photographs aren't better.

So, OK, reasons why you probably won't want to buy this book unless you collect books about bones (as opposed to having a library of carefully selected volumes):

- The photographs are terrible. I'd like to be able to say that a good deal of the problems (flatness, darkness, poor reproduction) are the fault of the book's production values and not of the photographer, but a good photographer should be able to get enough depth of field so that all parts of a bone are in sharp focus. I could overlook out-of-focus areas on something like a skull, which has considerable volume, but most elements only need a few inches. In a studio, with the right lens, there shouldn't be focus problems.

- The text is not all that useful. In a book like this, there should be arrows pointing out key similarities and differences to look for, summarized below each photograph. And the essays included are either not detailed enough, or don't seem to relate directly to the purpose of the photographs.

- The comparisons are sometimes a bit odd. While most of the photographs compare the same element between human and an animal, sometimes they show different sides (a left compared to a right, for example), sometimes the orientation of the bone is different (side view of one compared with front view of another, say), and sometimes an element is left out altogether. Some of this is no doubt due to availability of specimens, but still.

I'm going to stop pointing out the negatives here, because I'm starting to feel mean. I don't regret buying Comparative Skeletal Anatomy--where else am I going to find a comparison of human and duck bones?--but I can't recommend it unless you're a collector like me. Or unless it's the only book you can find on the subject.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)